This post is the fourth part on a small series on cellular automata and graph based systems as found in games. Part 1 can be found here, part 2 is over here and part 3 is here. Especially parts 1 and 2 are worth reading if you’re just catching up.

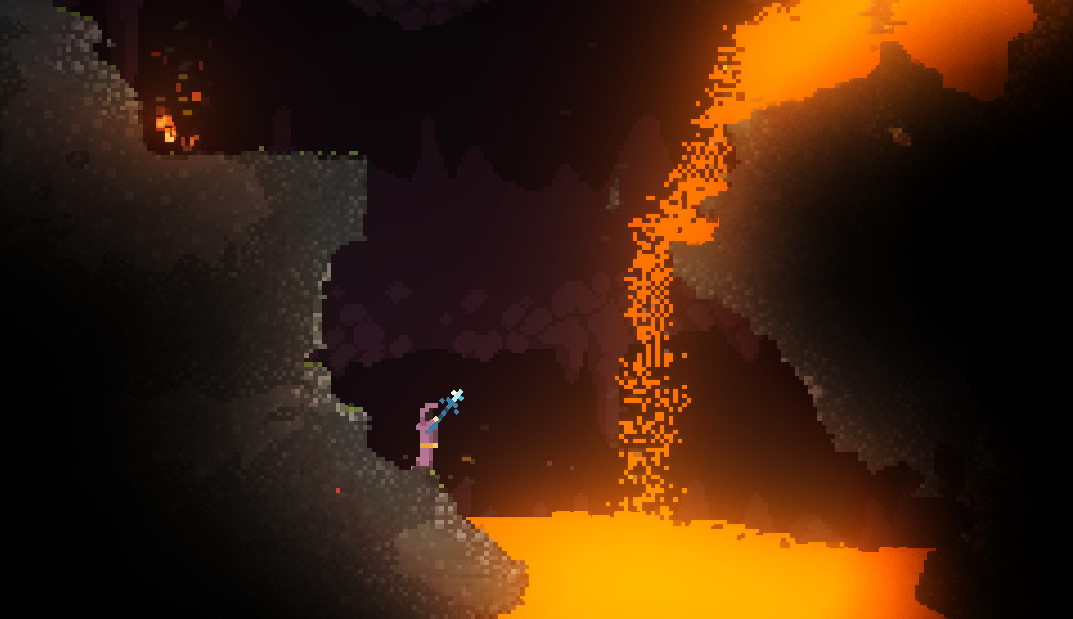

This series started at the end of 2017 and was finished in 2018 (time flies). This part was hence unplanned but I wanted to add some additional thoughts. Since I wrote the original series, Noita came out, a game which make the “falling sand” style of games part of its engine, proudly boasting that “every pixel is simulated”. It’s a very fun game, and a dream come true for fans of the cellular automaton (CA). Or is it?

Whilst playing the game, I was impressed with the engine being capable to simulate huge worlds, without slowing down (well — it does slow down, but only once you start unleashing real chaos). Based on some reading and some earlier discussion on Hacker News, it seemed to me that this was based on a traditional cellular automaton system, which can be easily made multi-threaded: just distribute the cells over the thread pool. As each cell’s new state is determined by its current environment, and all cells’ new state is calculated before “flipping the buffer”, this is easy.

However, given the scale of the game map, it also seemed that something more clever was going on. My hunch at the time was the grid is probably divided into blocks or chunks, with only the chunks close enough to the player being updated (or based on distance to other important triggers).

GDC to the Rescue

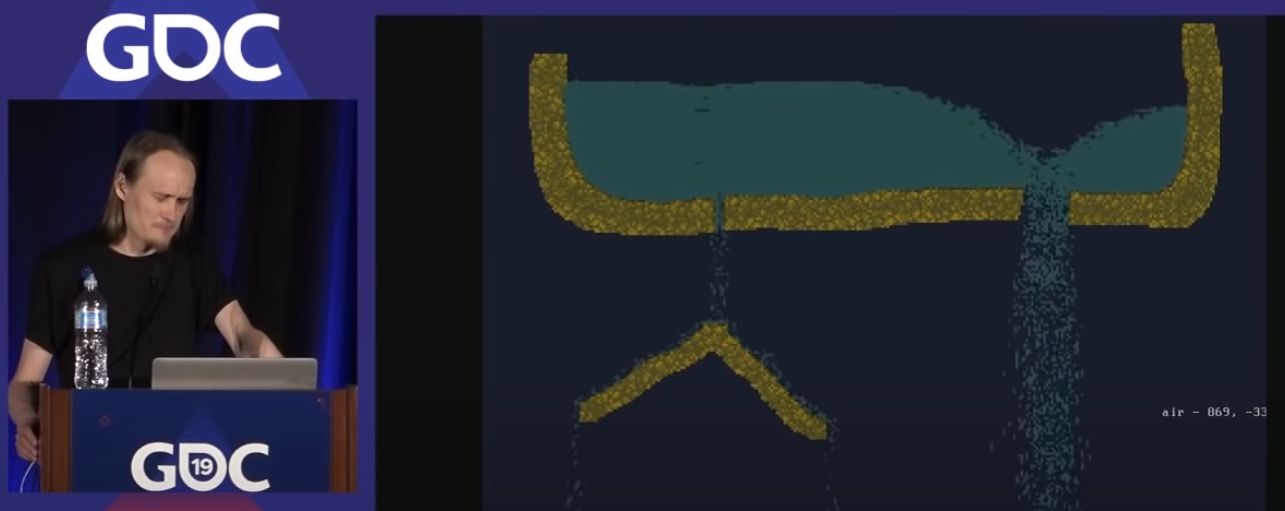

A couple of months ago, I returned to the topic and tried to investigate the Noita engine a bit more in depth. By then, the developers had given a presentation at GDC which I wholeheartedly recommend to watch for anyone with an interest in the topic. A couple of highlights stood out.

First, the speaker goes over the basics (and BASIC, too) of falling sand games quite extensively. This shows an implementation which does not rely on a real CA, but rather on a single-buffered version of the game which loops over the grid bottom-up, something like this:

for each row starting from bottom:

for each column:

if there's sand at (row, column):

drop it down if there's empty space

drop it down-right if there's empty space

drop it down-left if there's empty space

This works fine if you’re only simulating a couple of materials (sand and empty space) which behave similarly.

It is still relatively easy to add in water, which is very much like sand, except that:

for each row starting from bottom:

for each column:

if there's sand at (row, column):

drop it down if there's empty space

drop it down-right if there's empty space

drop it down-left if there's empty space

else if there's water at (row, column):

drop it down if there's empty space

drop it down-right if there's empty space

drop it down-left if there's empty space

move it right if there's empty space

move it left if there's empty space

Sound’s easy right? Well, if you’re like me and have spent a couple of hours implementing a CA-style engine to do this, you might argue:

- What if we want sand to float to the top of water? Can non-empty pixels displace each other?

- Based on the

for each columnloop, water will have a tendency to move right-wards (or left-wards, which-ever check is performed first) - How does this scale to more materials with more complex interactions?

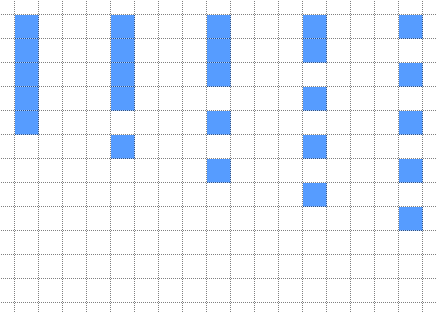

- Specifically, what if we add gasses which should go upwards? The whole reason one typically implements a bottom-up loop is because of the assumption of gravity. If we would go top-down, the simulation will quickly enter a gap-pattern:

The figure above shows five steps of a simulation where we’d be using a top-down loop. In the first time step, we’ve just drawn five water droplets above each other. For the second frame, the game loops over the first four, but can’t move them down (assume we’re moving downwards only for now) as there’s another pixel blocking them. The fifth (lowest) pixel can be moved down. For the third frame, the same problem occurs again for the top three pixels. The second to last pixel can be moved down (as there’s an empty spot not), and the fifth pixel can be moved down as well. This naturally leads to a dispersed one-in-between pattern.

Hower, with materials moving upwards (e.g. steam), the issue will reappear with a bottom-up style loop.

So okay, let’s argue that it’s a simplification for the sake of the presentation, as we can observe that the Noita engine is more involved. Let’s continue. The presenter shows a simple game with only one simulated liquid (blood), but with a nice trick that rigid physics bodies can interact with pixels and displace them further away.

When the player jumps in the blood, it takes the surrounding pixels and puts them in a particle simulation with velocity and gravity. This can make liquids look less blobby and we’re still using this. [paraphrased]

This is extremely neat. We won’t dive into that idea here, but might later. The approach to move pixels into a particle simulation is interesting, as well as the interaction with rigid bodies which themselves can be placed in and out the simulation by applying marching squares is very nice (as shown later in the presentation).

Next up, the multithreading aspect is discussed. To do so, the world is indeed divided into chunks. Each chunk keeps a dirty rect of things to be updated to limit the simulation. It gets a bit technical here, but something crucial is revealed:

The problem with adding multithreading is that it uses the same buffer. There’s no two buffers. So you need to make sure the same pixel is not updated by multiple threads. [paraphrased]

The solution presented is a checkboard style update, but what stood out to me was the fact that the approach taken is still a single buffer, pixel-oriented approach, very much in line with the BASIC example showed earlier. There’s one last notable remark here.

We guarantee that no pixel can be moved more than 32 pixels away. [paraphrased]

In summary, the talk is very revealing. The remainder of it goes over the design. It does leave us hanging a bit in terms of the exact details and whether Noita really doesn’t use a CA approach. One of the audience members in fact asks the same question (around 28:00):

You mentioned that the simulation is single buffered, did you try double buffering? - This is just how we got going. But later on I also noticed that when you do double buffering, you have to update everything even when applying multi threading. - I think you can do all sorts of simulations double buffered, but it seems much harder as you need to figure out where each pixel needs to go. [paraphrased]

It’s a quick question and a quick answer, but it completely threw me off after the first watching. Indeed, when you double buffer, you’d basically have to update the entire grid. This is what the multi threaded CA solution as mentioned at the beginning boils down to. The second part of the answer is even more revealing and contradictory for CA-fans, in the sense that it’s not really about figuring out where each pixel needs to go, it’s about how the state of each grid cell should change based on its environment. That is a fundamentally different approach, but on the other hand I can’t argue with practice: the Noita engine takes the pixels-as-objects approach and works.

So how does it work and maintain a believable simulation?

Looking for Solutions

The next step was trying to Google around for open source implementations of the idea, directly inspired by the talk. The only solid thing (well, apart from older falling sand games, of course), was this reddit discussion as well as this one. As always, not everything is directly helpful:

My surprise was that they don’t double buffer. Most programs involve drawing to a buffer rather than directly on screen when the frame is being assembled.

As commenters argue, the discussion has nothing to do with double or triple frame buffering. We’re only talking about the pixel simulation engine. The actual drawing routines are of course multiple-buffered and draw UI as well as particle elements on top. In fact, we’ve just seen how a lot of Noita’s believability comes from a particle system which pretends its adding in simulated pixels. Spell, splash, and explosion effects for instance. That’s an amazing feat in itself, but we’re razor focused on the simulation engine here.

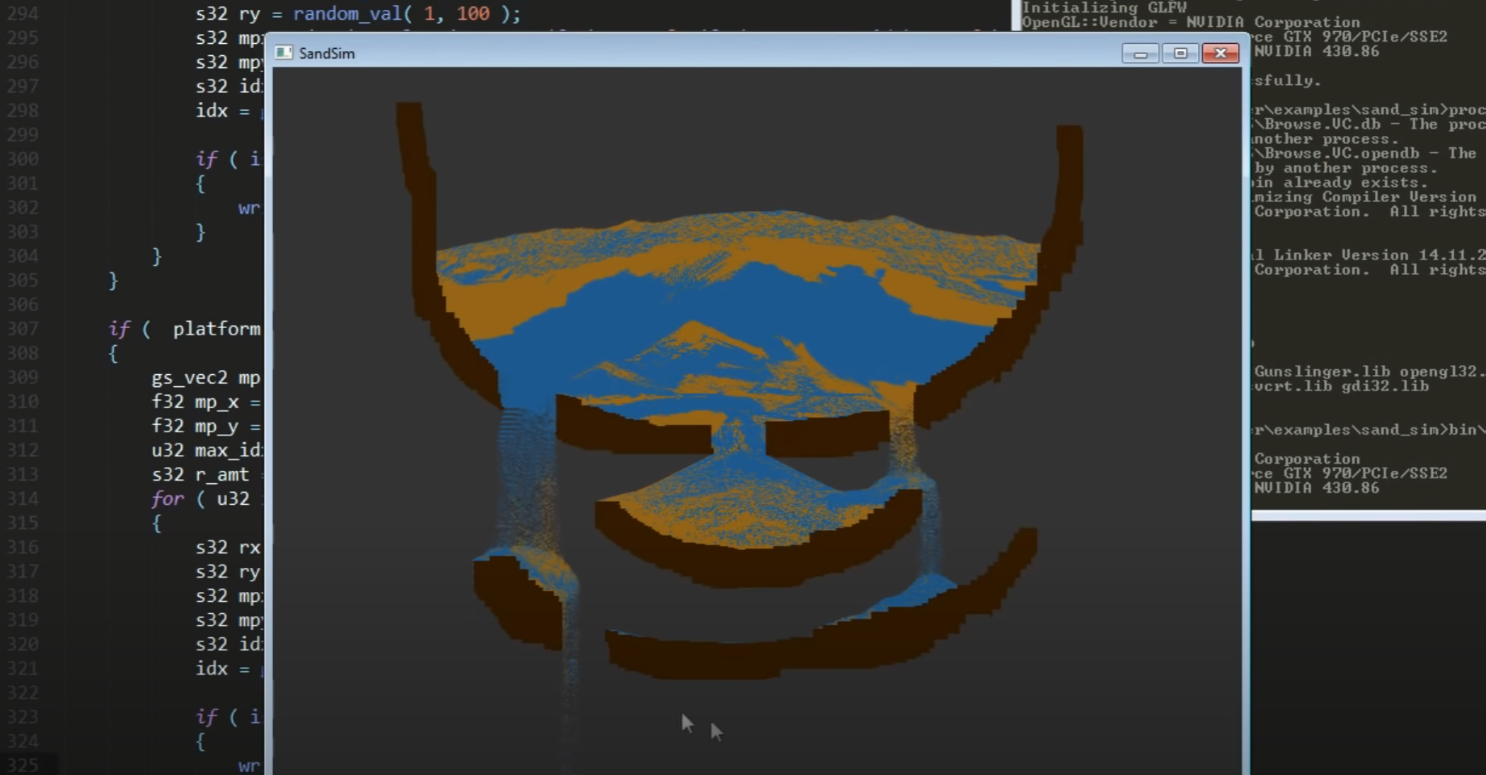

Stuck deep in some of those comments, I also found this YouTube video (Recreating Noita’s Sand Simulation in C and OpenGL | Game Engineering) which actually puts out code and tries to follow the same approach. And what do you know, it looks like it works:

I especially like how the sand mingles with the water. This is exactly what I was referring to above and the GDC video didn’t directly address. Noita heavily simulates materials with different densities, so in case you want to simulate pixels-as-objects, they need to be able to displace other pixels.

Fantastically, the author of the video also makes their code available. A quick perusal through the source code confirms it follows very much the non-CA style, and we can play around with the binary. The simulation is very solid (even although the code reveals that the author also had a hard time with some aspects which arise in a single-buffered engine):

What I especially like is that here too, materials are displaced and are moving further away than their immediate Moore neighborhood. At first, this sounds messy to simulate, but the Noita video shows the same thing:

In fact, this helps to alleviate the problem of the “gap” pattern as mentioned above. The result is somewhat more random, looking movement, but actually helps to increase realism.

I was kind off planning to leave it here and conclude that single-buffered pixel-as-object approaches are indeed a fine alternative for CA. Remember that the last thing we did was:

(You can play around with the simulation above. Pressing o cycles through the different material types to draw, p (un)pauses the simulation, d toggles debugging mode. Press r to reset everything. The initial setup loads in a closed system where water is heated, cycled, and cooled down.)

Even if this alternative sometimes encounters a situation where a pixel is destroyed (and hence cannot deterministally represent a closed loop system), it would be acceptable in a game environment.

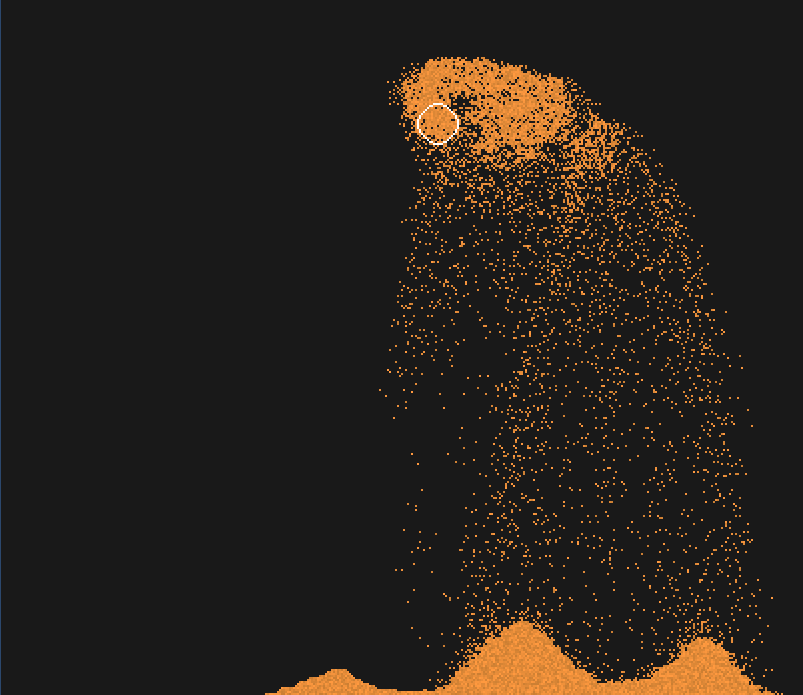

But there was one more thing I wanted to try. Image we make an hourglass style setup with sand at the top part and steam at the bottom, and then open up the middle part:

That’s no good. The steam particles are blocking the sand. Okay, this doesn’t happen with water, and steam disappears over time so this issue resolves itself quite quickly. Still, the Noita engine seems to be more clever here.

With that noted, I wanted to see what a minimal implementation which would be able to handle this would look like. To summarize, we’re going to start by implementing a single-buffer, pixels-as-objects, non-CA approach, without the particle system, rigid bodies, higher-than-Moore rank neighborhoods, multi-threading and shaders (which are used to make e.g. bodies of water more fluid-behaving). In other words, we won’t go nearly as far as Noita’s Falling Everything engine, but we do want to prove that the approach can work, and also illustrate some of the problems compared with a CA approach.

A Minimal Implementation

Let us start with a basic illustration. We’re going to construct a grid of cells, allow for three types of materials (walls, sand, and water), and then simply loop over each pixel from bottom to top like so:

visit_grid(func) {

var self = this;

for (var y = this.nrRows - 1; y >= 0; y--)

for (var x = 0; x < this.nrCols; x++)

func(self, x, y);

}

visit_pixels(func) {

this.visit_grid(function (w, x, y) {

var p = w.getPixel(x, y);

if (p) func(w, x, y, p);

});

}

We can then update all pixels every game loop:

this.world.visit_pixels(function (w, x, y, p) {

w.update(p);

}, true);

With our update function looking like so:

update(pixel) {

var checkMoves = [];

var firstSide = 1;

var secondSide = -1;

if (pixel.material.name != 'wall') {

checkMoves.push([pixel.x, pixel.y + 1]);

checkMoves.push([pixel.x + firstSide, pixel.y + 1]);

checkMoves.push([pixel.x + secondSide, pixel.y + 1]);

}

if (pixel.material.name == 'water') {

checkMoves.push([pixel.x + firstSide, pixel.y]);

checkMoves.push([pixel.x + secondSide, pixel.y]);

}

for (var move of checkMoves) {

if (!this.inBounds(move[0], move[1])) continue;

var destIsPixel = this.pixels.has([move[0], move[1]]);

if (!destIsPixel) {

this.movePixel(move[0], move[1], pixel);

break;

}

}

}

Sand can move down, down-left and down-right. Water can also move sideways. Note that the order of the checkMoves array matters. For now, we also only allow pixels to move to empty spots. We’ll change that later.

You can play around with the result below:

Obviously, this is not perfect yet (you’ll note that sand stacks on top of water), but before we fix that, there are a couple of other things to take care of. First of all, take a look at what happens if we drop water:

Not only does the water not flow naturally (it jumps to the right end), it also creates a strange horizontal gap pattern. The reason why this happens is due to the order by which we go over the columns in each row:

visit_grid(func) {

var self = this;

for (var y = this.nrRows - 1; y >= 0; y--)

// From left to right

for (var x = 0; x < this.nrCols; x++)

func(self, x, y);

}

And how we defined our moves for water:

if (pixel.material.name == 'water') {

checkMoves.push([pixel.x + firstSide, pixel.y]); // Check right hand side

checkMoves.push([pixel.x + secondSide, pixel.y]); // Check left hand side

}

Imagine we have two water pixels with an empty space in between. Since we check from left to right, and we prefer to move right first, water will have a tendency to end up right-sided. Once there, the water creates gaps in between drops. The reason for this is because we first attempt to move a pixel to the right, then go right one step (which now has the previous pixel), can’t move it right again, so move it left, back to its original spot.

We need to solve this problem first. Perhaps, once we have moved a pixel once in the current loop, we should avoid moving it again in the same update. So we will use a dirty flag for pixels which gets set to false before each update, and then set to true once we have moved a pixel. Our update function then skips over dirty pixels.

You can play with the result below:

This stops the gap pattern, somewhat. Instead, we now get this oscillating back-and-forth behavior:

Additionally, water still doesn’t flow very naturally:

This is an issue which is hard to solve with single buffered simulation approaches, and is not trivial to fix. One common way is to alternate the direction of the update loop, e.g. based on the frame counter (in fact, the code we found above also does so):

visit_grid(func) {

var self = this;

for (var y = this.nrRows - 1; y >= 0; y--)

for (var x = frameCount % 2 == 0 ? 0 : this.nrCols - 1;

frameCount % 2 == 0 ? x < this.nrCols : x >= 0;

frameCount % 2 == 0 ? x++ : x--)

func(self, x, y);

}

Another way is to randomize the order in which moves are checked:

var firstSide = random() < 0.5 ? 1 : -1;

var secondSide = firstSide < 0 ? 1 : -1;

This helps a bit, but still leads to behavior which is somewhat erratic (i.e. it can take a long time before a mass of water finds its stable, settled position):

Improving the Simulation

How do we continue to improve the simulation to make this behave a bit better?

Basically, we’d like to solve the following issues for our water. First, we’d like it to flow downwards where possible as quick as possible. Second, once it has reached a stable state, we’d like to avoid some pixels from erratically moving left and right forever. Third, we also want a row of water to be neatly filled up when possible, without in-between gaps.

For the first problem, we could for instance consider higher-than-Moore rank neighborhoods, e.g. have water flow downwards move than one pixel away if there’s no solid blocking the path. This is what Noita and the code we found does. This could be done with a simple line ray check using Bresenham’s line algorithm. Alternatively, we could also go for a more full-on particle-simulation where we give each pixel a velocity vector. If we ensure this to be below the unit vector in size, pixels can still spread around in all directions but cannot mvoe past walls.

The second problem could be avoided by checking if there is an empty spot available in the row under the pixel the pixel could eventually end up at. This is an extensive check though, and if resort to implementing this, we’d actually not be far away from implementing realistic pressure.

However, we can also improve our situation by means of a simpler heuristic. That is, let’s assign assign each pixel a velocity vector as mentioned above, but let us bound it to point to the right or left only. When we do a move check, we prefer trying going in the same direction first for each pixel. When we bump into something at the same height of us, we wait one world update iteration before checking the moves again but already change the velocity to point to the other side:

for (var move of checkMoves) {

if (!this.inBounds(move[0], move[1])) continue;

var destIsPixel = this.pixels.has([move[0], move[1]]);

var sameHeight = move[1] == pixel.y;

if (!destIsPixel) {

this.movePixel(move[0], move[1], pixel);

break;

} else if (sameHeight) {

// Bump

pixel.lastvel = -pixel.lastvel;

break;

}

}

The reason why we do the latter is because if we wouldn’t, we would again get oscillating one-gap patterns. We now arrive at an outcome which doesn’t handle all that badly:

One thing you’ll notice is that water pixels will still glide along a surface without ever settling down. If you look closely, this also sometimes happens in Noita and even in the example we found previously (although it is hard to see due to the pixels being so small). To resolve this, we could have pixels settle down once they’ve moved (in the same row) for n steps, and bring them back to life if e.g. their neighborhood changes. For now, we’ll leave this is as.

Handling Densities

The next thing we need to tackle is believable material interaction. Let’s first add a couple more materials:

const WallMaterial = new Material('wall', 10.0, '#8a522b', true);

const RockMaterial = new Material('rock', 5.0, '#7d6d61', true);

const SandMaterial = new Material('sand', 3.0, '#edc677', true);

const LavaMaterial = new Material('lava', 2.0, '#852220', false);

const WaterMaterial = new Material('water', 1.0, '#77b0ed', false);

const OilMaterial = new Material('oil', 0.5, '#ada88e', false);

const SteamMaterial = new Material('steam', 0.1, '#bee6e5', false);

The second argument here refers to the density. The heavier, the more we want to have it float to the bottom. However, only gasses and water interact in this way.

We rework or update loop as follows (this getting a bit messy, but let’s keep it as is for the sake of showing one function):

update(pixel) {

var checkMoves = [];

var firstSide = pixel.lastvel;

var secondSide = -firstSide;

if (pixel.dirty) return;

if (pixel.material.name != 'wall' && pixel.material.name != 'steam') {

checkMoves.push([pixel.x, pixel.y + 1]);

}

if (pixel.material.name == 'steam') {

checkMoves.push([pixel.x, pixel.y - 1]);

checkMoves.push([pixel.x + firstSide, pixel.y - 1]);

checkMoves.push([pixel.x + secondSide, pixel.y - 1]);

}

if (pixel.material.name == 'sand'

|| pixel.material.name == 'lava'

|| pixel.material.name == 'water'

|| pixel.material.name == 'oil') {

checkMoves.push([pixel.x + firstSide, pixel.y + 1]);

checkMoves.push([pixel.x + secondSide, pixel.y + 1]);

}

if (pixel.material.name == 'lava'

|| pixel.material.name == 'water'

|| pixel.material.name == 'oil'

|| pixel.material.name == 'steam') {

checkMoves.push([pixel.x + firstSide, pixel.y]);

checkMoves.push([pixel.x + secondSide, pixel.y]);

}

for (var move of checkMoves) {

if (!this.inBounds(move[0], move[1])) continue;

var destPixel = this.pixels.get([move[0], move[1]]);

var destIsPixel = this.pixels.has([move[0], move[1]]);

var destIsEqualY = move[1] == pixel.y;

var destIsHigherDensity = destIsPixel && destPixel.material.density > pixel.material.density;

var destIsLowerDensity = destIsPixel && destPixel.material.density < pixel.material.density;

if (!destIsPixel) {

this.movePixel(move[0], move[1], pixel);

break;

} else if (!destPixel.material.solid &&

((destIsHigherDensity && move[1] <= pixel.y) ||

(destIsLowerDensity && move[1] > pixel.y))) {

this.movePixel(move[0], move[1], pixel);

break;

} else if (destIsEqualY) {

pixel.lastvel = -pixel.lastvel;

break;

}

}

}

And this is the result. Try playing around with water, steam, and oil and see how they interact:

(Of course, the real world is always more complex, even when aiming to handle the simplest concepts only. Sand, for instance, is in a kind of intermediate solid-fluid state where it actually would disperse in a different way under water. It’s actually a very hard case for physics in general.)

Adding Interactions

We’re almost done. The only thing left to do is add in a couple of interactions. Here is where we finally encounter a huge benefit of our single buffer approach. Contrary to a CA system, these are very easy to add in. We first give each pixel a life time which gets incremented every world update, and then simply slap in the following in our update function (we also add two new materials: wood and fire):

update(pixel) {

var checkMoves = [];

var firstSide = pixel.lastvel;

var secondSide = -firstSide;

if (pixel.dirty) return;

pixel.lifetime++;

if (pixel.material.name != 'wall' && pixel.material.name != 'wood'

&& pixel.material.name != 'steam') {

checkMoves.push([pixel.x, pixel.y + 1]);

}

if (pixel.material.name == 'steam' || pixel.material.name == 'fire') {

checkMoves.push([pixel.x, pixel.y - 1]);

checkMoves.push([pixel.x + firstSide, pixel.y - 1]);

checkMoves.push([pixel.x + secondSide, pixel.y - 1]);

}

if (pixel.material.name == 'sand'

|| pixel.material.name == 'lava'

|| pixel.material.name == 'water'

|| pixel.material.name == 'oil'

|| pixel.material.name == 'fire') {

checkMoves.push([pixel.x + firstSide, pixel.y + 1]);

checkMoves.push([pixel.x + secondSide, pixel.y + 1]);

}

if (pixel.material.name == 'lava'

|| pixel.material.name == 'water'

|| pixel.material.name == 'oil'

|| pixel.material.name == 'steam'

|| pixel.material.name == 'fire') {

checkMoves.push([pixel.x + firstSide, pixel.y]);

checkMoves.push([pixel.x + secondSide, pixel.y]);

}

// Special case for fire

if (pixel.material.name == 'fire') {

checkMoves = shuffle(checkMoves);

}

for (var move of checkMoves) {

if (!this.inBounds(move[0], move[1])) continue;

var destPixel = this.pixels.get([move[0], move[1]]);

var destIsPixel = this.pixels.has([move[0], move[1]]);

var destIsEqualY = move[1] == pixel.y;

var destIsHigherDensity = destIsPixel && destPixel.material.density > pixel.material.density;

var destIsLowerDensity = destIsPixel && destPixel.material.density < pixel.material.density;

// Interactions

if (destIsPixel) {

if (pixel.material.name == 'lava' && destPixel.material.name == 'water') {

destPixel.material = SteamMaterial;

pixel.lifetime = 0;

}

if (pixel.material.name == 'lava' && destPixel.material.name == 'wood') {

destPixel.material = FireMaterial;

pixel.lifetime = 0;

}

if (pixel.material.name == 'lava' && destPixel.material.name == 'oil') {

destPixel.material = FireMaterial;

pixel.lifetime = 0;

}

if (pixel.material.name == 'water' && destPixel.material.name == 'steam') {

destPixel.material = WaterMaterial;

pixel.lifetime = 0;

}

if (pixel.material.name == 'fire' && destPixel.material.name == 'wood') {

destPixel.material = FireMaterial;

pixel.lifetime = 0;

}

if (pixel.material.name == 'fire' && destPixel.material.name == 'oil') {

destPixel.material = FireMaterial;

pixel.lifetime = 0;

}

if (pixel.material.name == 'fire' && pixel.lifetime >= 30) {

pixel.material = SteamMaterial;

pixel.lifetime = 0;

break;

}

if (pixel.material.name == 'steam' && pixel.lifetime >= 100) {

this.removePixel(pixel);

break;

}

if (pixel.material.name == 'lava' && pixel.lifetime >= 300) {

pixel.material = RockMaterial;

pixel.lifetime = 0;

break;

}

}

// Movement

if (!destIsPixel) {

this.movePixel(move[0], move[1], pixel);

break;

} else if (!destPixel.material.solid &&

((destIsHigherDensity && move[1] <= pixel.y) ||

(destIsLowerDensity && move[1] > pixel.y))) {

this.movePixel(move[0], move[1], pixel);

break;

} else if (destIsEqualY) {

pixel.lastvel = -pixel.lastvel;

break;

}

}

}

We cheat a little bit by shuffling the movement candidates in the case of fire to make it behave more erratic, but other than this, the interactions are very self explanatory.

Here you can see me playing around with the result a bit:

And if you want to try for yourself:

Done For Now

This has been a long post. The code fragments might seem out of place but you can easily inspect the non-obfuscated JS code in each of the iframes above should you want to.

There’s a couple of noteworthy things still to tackle:

- Note that the bottom-up world update still stands. This means that e.g. steam has a tendency to immediately disperse when drawn in a vertical line (you can see this above). Luckily, this doesn’t look too bad for gasses

- We haven’t dealt with higher order neighborhoods at all. See the discussion on this above. However, this wouldn’t be too hard to add in at this stage, and we might do so in an eventual next part. More generally, we might want to go towards a more realistic particle-style approach where we give each pixel a real velocity vector. This could also help to “splash up” liquids when a solid falls into them

- Multithreading hasn’t been dealt with at all — but this is deliberately not a focus here. I’m also quite honestly incapable to implement this in JavaScript and p5.js

- The same goes for shaders and more effects. Again, this is a bare-bones as close to the basic simulation as we can get exercise. Not a full game engine

- And similarly, rigid body physics are not dealt with at all

- However, I am now convinced that single buffered simulation engines can be a viable and workable alternative for cellular automata. This comes with a lot of drawbacks (oscillation and so on), but also has nice benefits (interactions, more straightforward coding, faster)

- Finally, something fun which we did tackle in an earlier part but didn’t do here was pressure. I mentioned above that even a heuristic approach to do this (Dwarf Fortress style) is quite expensive. However, I do have a weird alternative idea for this: what if we not only adopt a full-on particle systems for the pixels but perhaps also simulate each particle as a unit circle in a more modern physics engine with mass determined by the distance from the bottom row? This could be easily investigated with something like Box2D, I think. Maybe also something for later

In any case, these are enough points to discuss for an optional Part 5, should it arrive.