This post is the third part on a small series on cellular automata and graph based systems as found in games. Part 1 can be found here, part 2 is over here.

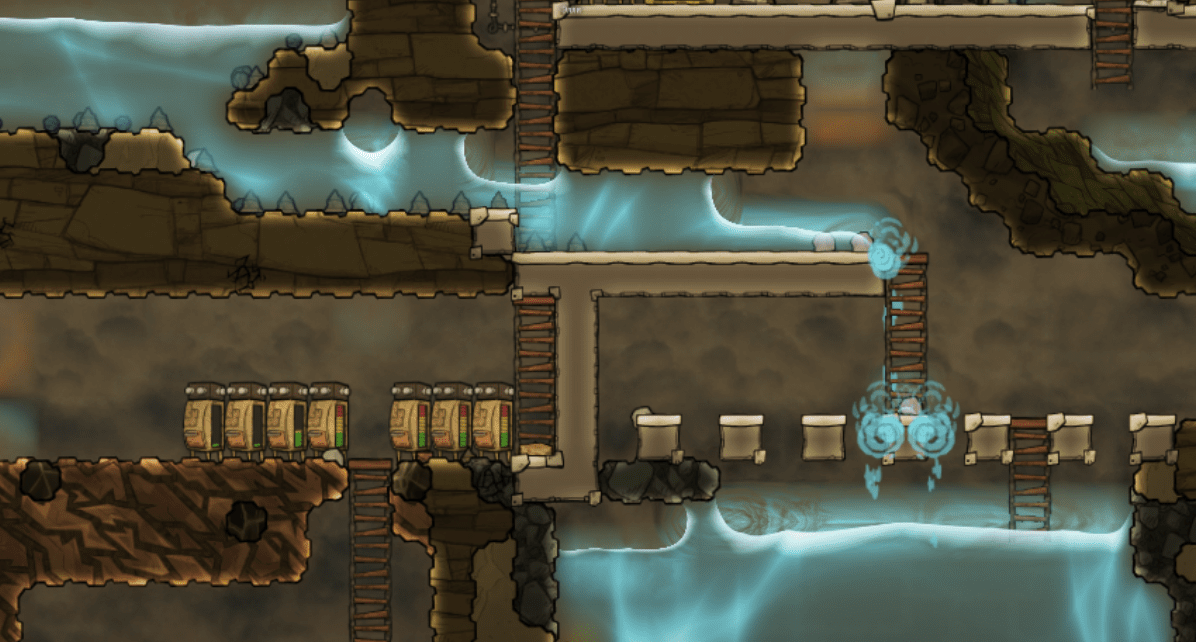

In our last part, we ended up with the basic groundwork to construct grid based cellular automata, including fluid dynamics as seen in games such as Oxygen Not Included.

Here’s what we ended with last time around. (Pressing o cycles through the different material types to draw, p (un)pauses the simulation, d toggles debugging mode. Press r to reset everything.)

Apart from using cellular automata based systems, many game will also incorporate graph based gameplay mechanisms on top of this, e.g. to model the behavior of agents, electricity, or modeling flow through pipes, such as in Cities: Skylines, SimCity, and many others:

Graphs

The field of graphs and their theory forms a whole maths subfield on their own. Put simply, a graph is a structure describing objects, called vertices (or nodes) and the relations between them, called edges (or lines, or arcs), which can be directed (if the ordering of the connected nodes is important) or undirected.

An interesting avenue to explore is whether we can model such structures using our grid-based cellular automata we have already explored before. Let us take the example of the following system you might encounter in a typical game:

- “Emitter” nodes send water (or some other sort of packets) every so often

- Water flows through edges (the pipes, if you will) through connected nodes

- “Connecting” nodes link multiple pipes together, when water passes through these, they’ll send it along to one of the connected pipes in a round robin fashion

- “Consumption” nodes remove the water upon arrival

Trying to implement this in a cellular automata fashion is possible, and looks like this:

This being said, the limitations of the system rapidly become clear. We need a whole lot of state to keep track of the system as it updates (including defining a water packet having a “tail”, similar to the Wireworld example seen earlier), and the rule set is nothing short of messy:

- Define the neighborhood as a Von Neumann neighborhood

- If the current cell is an edge, and there is an emitter in the neighborhood ⇒ change the cell to a spawn

- Otherwise, if there is a head in the neighborhood ⇒ change the cell itself to a head

- Otherwise, if there is a connector in the neighborhood ⇒ change the cell itself to a head

- If the current cell is an emitter ⇒ rotate its direction

- If the current cell is a spawn ⇒ change it to a head

- If the current cell is a head ⇒ change it to a tail

- If the current cell is a link and not on cooldown, and there is a head in the neighborhood ⇒ add one to its counter

- If the current cell is a link and its counter is above zero, and there is an edge in its neighborhood ⇒ detract one from its counter and put it on a cooldown

- If the current cell is a link and its counter is above zero ⇒ rotate its direction

- If the current cell is a link and on cooldown ⇒ remove its cooldown

Phew, that is a lot of state keeping to model a simple system. Perhaps we can do better by switching to a graph-first approach.

Let us start with a basic playground where we can add nodes and connect them (click to add or remove a node, drag between two nodes to add an edge):

This breaks away from our grid-based mentality, though this is less of an issue as it seems as we can simply map the concept of a graph to a grid as well by constraining nodes to grid positions as well.

Moving objects

This basic system is enough to set up a system for moving packets across our graph. In its most basic form, it is sufficient to define a strategy in terms of what should happen when a node should emit a packet, and what should happen when a node consumes a packet (i.e. when a packet arrives at its destination node).

A random strategy would look as follows:

function emitPacket(n, from) {

var connected = getConnected(n);

if (connected.length == 0) return null;

var next = undefined;

while ((from == next && connected.length > 1) || next == undefined) {

next = connected[randomint(0, connected.length)];

}

var newPacket = new Packet(n, next);

packets.push(newPacket);

}

function consumePacket(p) {

var n = packets[p].to;

var connected = getConnected(n);

if (connected.length > 1) emitPacket(n, packets[p].from);

packets[p].remove()

}

Note that we already account for a simple system where nodes should prevent sending packets to a node equal to where the packet just came from.

The result looks as follows (click to add or remove a node, drag between two nodes to add an edge, press middle mouse button on a node to have it start emitting packets):

A round robin strategy is relatively easy to implement as well:

function emitPacket(n, from) {

var connected = getConnected(n);

if (connected.length == 0) return null;

var next = undefined;

while ((from == next && connected.length > 1) || next == undefined) {

nodes[n].last_connected_index = (nodes[n].last_connected_index + 1) % connected.length;

next = connected[nodes[n].last_connected_index];

}

var newPacket = new Packet(n, next);

packets.push(newPacket);

}

function consumePacket(p) {

var n = packets[p].to;

var connected = getConnected(n);

if (connected.length > 1) emitPacket(n, packets[p].from);

packets[p].remove()

}

And this looks as follows:

Even more convoluted systems, such as packets moving along a shortest path to their destination is relatively easy to implement as well. We just calculate the shortest path using Dijkstra’s algorithm (to a random destination node, in this case) and store it in the packet’s state. On consumption, the consuming node uses this to send the packet along:

function emitPacket(n) {

var connected = getConnected(n);

if (connected.length == 0) return null;

var finaldest = randomint(0, nodes.length - 1)

var trajectory = dijkstra(n)[finaldest];

if (trajectory.dist == 0 || trajectory.dist == Infinity) return;

var newPacket = new Packet(n, trajectory.shift());

newPacket.trajectory = trajectory;

packets.push(newPacket);

}

function consumePacket(p) {

var n = packets[p].to;

if (packets[p].trajectory.length > 0) {

var newPacket = new Packet(n, packets[p].trajectory.shift());

newPacket.trajectory = packets[p].trajectory;

packets.push(newPacket);

}

packets[p].remove()

}

And this looks as follows (middle click once on a node to emit one packet):

Towards more complex systems

We can now extend this system with some more complex rules as well. As an example, consider a game like Harvest: Massive Encounter or Creeper World where players connect up an energy grid. An emitter sends energy packets along to outer nodes, though connecting nodes need to be powered up themselves before they can send energy along. As a routing system, we’ll use a simple random strategy:

function emitPacket(n, from) {

var connected = getConnected(n);

if (connected.length == 0) return null;

var next = undefined;

while ((from == next && connected.length > 1) || next == undefined) {

next = connected[randomint(0, connected.length)];

}

var newPacket = new Packet(n, next);

packets.push(newPacket);

}

function consumePacket(p) {

var n = packets[p].to;

if (node_energy !== null && !(nodes[n].id in node_energy)) node_energy[nodes[n].id] = 0;

if (node_energy !== null && node_energy[nodes[n].id] < energyRequired.value()) {

node_energy[nodes[n].id] += packetEnergy.value();

} else {

var connected = getConnected(n);

if (connected.length > 1) emitPacket(n, packets[p].from);

}

packets[p].remove()

}

Feel free to play around with the result below (click to add or remove a node, drag between two nodes to add an edge, press middle mouse button on a node to have it start emitting packets, or middle click outside to stop emitting). Note how in the default scenario, our outermost nodes already are hard to power up using a random routing strategy. Try playing around with the parameters to observe the results:

This concludes our very shallow tour around cellular automata and graphs in games. As noted in the introduction, this was mainly meant to play around a bit with p5.js to visualize and create such systems. The underlying code is too messy to publish in full, though hopefully has shed some light on how these systems form recurring building blocks in many games.