(This is the first part in the University Of Waterloo CS Club Tron Challenge post series. You can find the second part here.)

The Computer Science Club of the University of Waterloo is currently organizing an AI challenge, sponsored by Google. I’m (as always) a bit late with my write-up and the contest will be ending soon (26th of February), so you will have to be quick if you still want to enter. However, I can imagine that many of you are already familiar with the contest…

Since this challenge combines some interesting topics: AI, a game, a contest and optimization, I thought it might be interesting to post some conclusions here. Note that many of the topics here are already discussed at other websites and blogs. I will post references and links to those. Consider this as a general overview, a journal of my own tries, and a closer look at some common pitfalls.

Introduction

The challenge this year was all about Tron. Tron is like two-player Snake, where your objective is to box in your opponent to force him to crash into a wall (or your or his own tail) before you do. Of course, this game was first introduced in the movie with the similar name: Tron.

In this version of the game, some things are a bit simpler then what we see in the movie above:

- Only two teams, with one player per team. In other words: one versus one.

- No acceleration: everyone moves at the same speed.

- No breaking the boundaries.

- Your tail doesn’t vanish once you crash. Even if this would happen, it wouldn’t matter (once you’ve crashed you’ve lost anyway and the game ends).

- The playfield doesn’t necessarily start empty.

(Note: it is possible to find many (free) games on the internet which do include some of these features.)

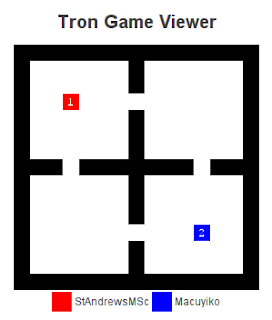

For example, one of the maps provided in the package looks like this:

########

#1 #

# #

# #

# #

# #

# 2#

########

# stands for a wall, and 1 and 2 are our two players on their starting positions.

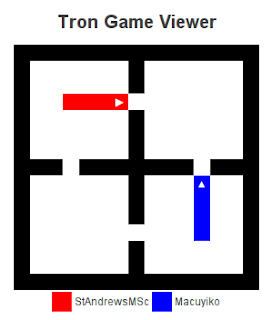

Let’s pit them against each other and see how they fare. We provide them with a very basic mode of intelligence: just pick any random direction if the space is free if possible.

After the first move, the board looks like this:

########

## #

#1 #

# #

# #

# 2#

# ##

########

See how they both leave a wall behind them? Note that diagonal moves are forbidden. A few moves later, the situation looks like this:

########

## #

## #

## #

### #

# 1 ###

# 2####

########

If player 1 now decides to go right, and player 2 decides to go up, they will crash into each other and the game will end with a draw. This actual run turns out to be a bit more dramatic:

########

## #

## #

## #

### #

#1#2 ###

# #####

########

Player 1 has gone left, and 2 has gone up and the players are now separated from each other. Unless player 2 does something really stupid, it is clear that 1 will lose…

########

## #

## #

## #

### #

####2###

#1 #####

########

...

########

## #

## #

## #

### 2 #

########

##1#####

########

Player 1 is completely trapped and crashes into a wall. Player 2 wins.

The objective of each participant is to write an AI which will have to play against the bots of the other players. The more you win, the higher you score…

Basic strategies

To help players start off, the website gives some basic strategies for your bot:

Random selection: as seen in the introduction: just pick an open space at random and move there. This is a bad strategy because often you will seperate yourself from your opponent, with less space to move in.

Ordered selection: make a list of directions, e.g. [north, east, south, west]. Pick the first possible direction from the list. This will not seperate you from your opponent as quick (or foolish) as random selection, but will eventually end up in a bad seperation otherwise.

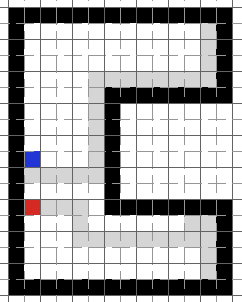

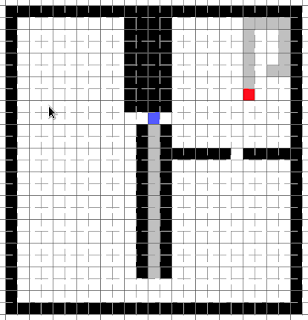

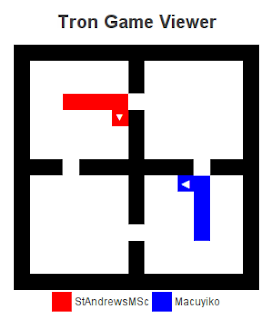

Wall hugging: always try to stay close to a wall. This strategy is interesting because it makes good use of the available space. However, it is not often perfect. Take for example a red player who finds himself in this position:

Now let’s assume that the player is a wall hugger: he prefers to be close to a wall at all times. Let’s also assume that if there are more available choices, he follows the left hand rule. After a few moves, the situation thus looks like (grey squares are the “tail” of the player):

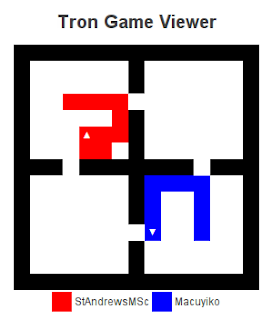

When we continue following the left hand rule (and still being close to a wall), we end up with:

Which is of course, not the optimal choice here. It is trivial to find other maps which break the left (or right, or ordered direction) wall hugging method.

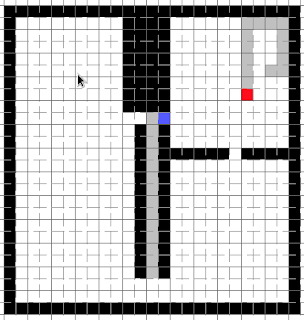

Wall hugging - another try: let’s see if we can fix the above problem. Let’s wallhug while following a rule (left or right hand, ordered direction or even random), but when we notice that a move would lead us into a new separate space which results in less possible moves than the other separated space, try the next move.

E.g., moving left in this scenario:

…would lead us into a new separated space with less empty cells than when we would have gone right. Will this strategy work? Let’s start again:

Let’s say we follow the left hand rule again. We just keep following the wall until:

Now, with our new rule in place, we will not go left, as this would separate us in a bad way from the other empty squares. We thus pick the next possible move, which is right. Note that this also separates us from the squares to our left, but since we have more moves in our space, this is no problem:

We continue following the wall until we see this:

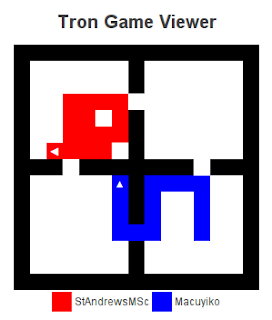

The left hand rule suggests us to go left. This separates our possibilities once again, but since left results in more empty spaces than going up, we can safely go left. This continues until we have no more moves left:

Not bad at all, the board was quite nicely filled. Still, we can do better. In fact, it is possible to end up like this:

This is clearly a much better way of filling the board (in fact, it is the best). Can you figure out how to do it? Can you figure out an algorithm to describe the behavior? Do you think your algorithm will work in all maps? Keep these questions in mind for later…

Enemy avoidance or chasing: run away from the enemy. Pick the direction which is farthest away from the opponent. We can also reverse this strategy: move as close to the opponent as possible. Both are easy to implement, so which one do we pick? In most maps, chasing will result in a draw against other chasers (suicidal behavior), and in a win against runners. Runners on the other hand will often draw against runners. Most player pick a chasing, aggressive bot. And since drawing is better than losing, we have no choice but to use an aggressive bot ourselves to increase our chances.

Most open destination: uses some simple rules to pick the direction which ends up giving us the most open spaces. We already used this a bit in our improvement of our wall hugging algorithm.

The website also mentions near and far strategies, but we’ll take a look at those later.

First conclusions

After evaluating the strategies above, we can already draft out a good simple strategy:

- When we’re not separated from the opponent: try to separate him into a space so that we have more remaining moves than him.

- Once we are separated: try to fill our available moves in the best possible way.

To find out if we’re separated (and our available spaces), we can use a flood fill algorithm. An implementation in Python could look like this:

def flood_fill(board, startpos):

expand = [startpos]

done = []

while len(expand) is not 0:

pos = expand.pop()

done.append(pos)

for dir in tron.DIRECTIONS:

dest = board.rel(dir, pos)

if board.passable(dest) and dest not in done and dest not in expand:

expand.append(dest)

return len(done)`

However, figuring out the number of empty squares is not enough. Once we know that we have more space, how do we proceed to fill this space in an optimal way. As we saw in the wall hugging strategy above, it turns out this is deceptively difficult. The Waterloo strategy page describes it best:

However, there are situations where flood-fill can be tricked into entering a trap: an area that looks big, but in which your bot cannot move freely. So, while this strategy works for most situations and is an easy addition to a good near strategy, it doesn’t cover all situations.

Longest-path approximation

What your bot is effectively trying to do in a survival situation is to find the longest path in the board starting at your current position.

Unfortunately, the longest-path problem itself is NP-complete, which means that, barring a miracle in Computer Science (namely, the unlikely result that P=NP), it is very difficult in general to find this longest path.

All hope is not lost, however: there are some decent approximations you can make which run reasonably quickly and avoid traps like those described above.

One such approach is based on articulation vertices on the board. An articulation vertex on a Tron board is a space which, if it were filled in by a wall or trail, would cut the area it is in into two or more disconnected areas. For a given square, if it is an articulation vertex which cuts the area into three or more disconnected areas, then it is impossible for your bot to visit all three areas, which gives you an easy way to determine how many squares are impossible to visit. By computing the articulation vertices in the board, you can obtain a better approximation of the number of free squares which can be visited, and thus fill your space more efficiently.

Keep the definition of articulation vertices in mind, we will mention this again later. I decided to use a simple but quick heuristic to figure out a way of filling the board. It’s quick and works good enough most of the times (meaning that once we’re seperated and have more empty space, we have a high chance of actually winning).

Now: what do we do if we’re not seperated…? On option is to use a minimax strategy.

Battle strategy: using minimax

Minimax is a decision rule which maximizes our potential gain while minimizing our possible loss. It can be used in two player games where it is possible to assign a value (or score) to each decision for each player.

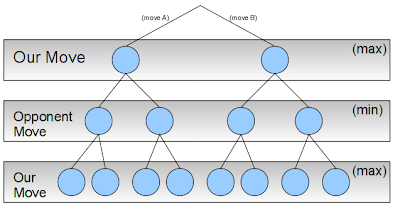

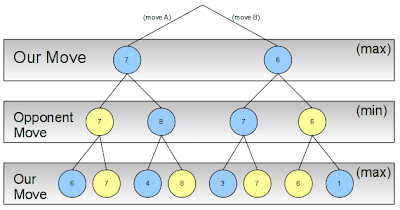

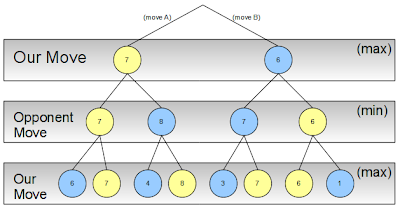

For example, let’s say we need to choose between two possible moves A or B, in a given game. If we think three levels deep, we might end up with something like this:

As you see in the search tree above, for each of our two moves A or B, our opponent can also make two moves. Then we move again. The strategy we’ll be following is max(imize our gain). Our opponent will try to min(imize our gain).

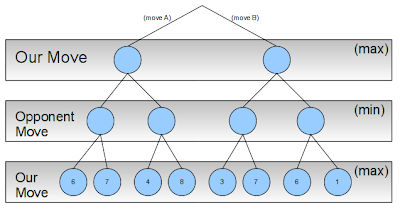

Once we’re at our desired (lowest) level in the tree, we assign a score to all the possible outcomes:

Our opponent knows that we will always pick the best (max) choice (in yellow) when confronted with a specific situation:

Our opponent will thus try to minimize our gains (he wants us to lose), so we know what he’ll pick for each of our moves (yellow):

At the top level it is now clear that, to maximize our gain we pick move A with a resulting score of 7, provided that our opponent will react in the smartest way possible:

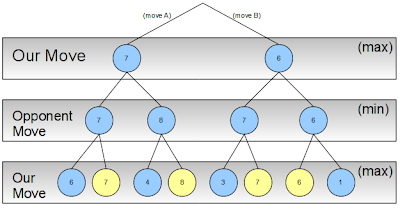

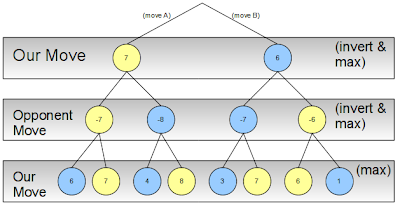

Since alternating between minimizing and maximizing the scores between each level of the search tree can be tedious to program, we can use the following observation to keep things simpler:

max(a,b) = -min(-a,-b)

Our example tree thus becomes:

By inverting the score each time we propagate upwards, we can use max at every level.

The strategy page recommends following a minimax strategy to avoid traps or dead ends. It is clear that, to create a winning minimax strategy, we must give sensible scores to each of the game states. A lot of players are thus using minimax strategies and doing well to very well with them.

It’s also fairly logical that the more levels you search, the higher your chance of winning becomes. However, since bots are only given one second to think before each move, exploring a high number of levels is impossible, especially in interpreted languages. It’s no wonder that many high-ranked players are using C++.

To speed up iterating the tree, we can use a technique called alpha-beta pruning. We can also use iterative deepening. I won’t explain those into detail here, but I can give you a handy list of resources:

- The Wikipedia page on Minimax gives examples and pseudocode.

- The Wikipedia page on alpha-beta pruning does the same for this technique. The pseudocode is not hard to implement once you understand minimax, and does speed things up a lot!

- Also iterative deepening is explained on Wikipedia; it’s easy to understand, but a bit harder to implement.

- Another contestant has explained his minimax strategy on his website. He does a fantastic job explaining the concepts above, and even provides a starting point for an evaluation function you can use to assign a score to the board.

- Jamie, another contestant, also discusses his techniques in his blog, he even links to some interesting Python source code.

- A quick Google search finds some interesting minimax and alpha beta pruning code written in Python. It plays Othello, but the AI and game logic are cleanly separated.

Before we continue: a quick look at some other projects

Now that we have a basic understanding of the workings of a Tron bot and strategy, we can Google around to see if we come up with some interesting projects using these methods. Let’s see what some of the open source Tron games are using as a strategy.

KTron‘s source can be viewed online. We notice the following comment:

// This part is partly ported from

// xtron-1.1 by Rhett D. Jacobs (rhett@hotel.[...])`

We thus take a look at xtron, you can find the source package here. main.c contains the think routine:

/* artificial intelligence routines for computer player */

void think(int p_num)

{

enum directions sides[2];

int flags[6] = {0,0,0,0,0,0};

int index[2];

int dis_forward, dis_left, dis_right;

dis_forward = dis_left = dis_right = 1;

switch (p[p_num].plr_dir) {

case left:

/* forward flags */

flags[0] = -1;

flags[1] = 0;

/* left flags */

flags[2] = 0;

flags[3] = 1;

/* right flags */

flags[4] = 0;

flags[5] = -1;

/* turns to either side */

sides[0] = down;

sides[1] = up;

break;

//...

}

/* check forward */

index[0] = p[p_num].co_ords[0]+flags[0];

index[1] = p[p_num].co_ords[1]+flags[1];

while (index[0] < MAXHORZ && index[0] >= MINHORZ &&

index[1] < MAXVERT && index[1] >= MINVERT &&

b.contents[index[0]][index[1]] == 0) {

dis_forward++;

index[0] += flags[0];

index[1] += flags[1];

}

if (dis_forward < LookAHEAD) {

dis_forward = 100 - 100/dis_forward;

/* check left */

index[0] = p[p_num].co_ords[0]+flags[2];

index[1] = p[p_num].co_ords[1]+flags[3];

while (index[0] < MAXHORZ && index[0] >= MINHORZ &&

index[1] < MAXVERT && index[1] >= MINVERT &&

b.contents[index[0]][index[1]] == 0) {

dis_left++;

index[0] += flags[2];

index[1] += flags[3];

}

/* check right */

index[0] = p[p_num].co_ords[0]+flags[4];

index[1] = p[p_num].co_ords[1]+flags[5];

while (index[0] < MAXHORZ && index[0] >= MINHORZ &&

index[1] < MAXVERT && index[1] >= MINVERT &&

b.contents[index[0]][index[1]] == 0) {

dis_right++;

index[0] += flags[4];

index[1] += flags[5];

}

if(!(dis_left == 1 && dis_right == 1))

if ((int)rand()%100 >= dis_forward || dis_forward == 0) {

/* change direction */

if ((int)rand()%100 <= (100*dis_left)/(dis_left+dis_right))

if (dis_left != 1) /* turn to the left */

p[p_num].plr_dir = sides[0];

else /* turn to the right */

p[p_num].plr_dir = sides[1];

else

if (dis_right != 1) /* turn to the right */

p[p_num].plr_dir = sides[1];

else

/* turn to the left */

p[p_num].plr_dir = sides[0];

}

}

}

It turns out this code is using a simple strategy. The difficulty of the game lies in the fact that player can move slow (easy) or very fast (very hard). The AI looks at the distance before reaching a wall while heading in its current direction. The closer it comes, the higher the chance of turning. When we’re next to a wall, the chance is, of course, 100%.

The code is easily converted to a Python bot:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 | |

Uploading the converted code to the contest server quickly confirms the fact that this bot is not doing well (in blue):

In this case, it’s lucky (in red):

A final search on Google code turns up some source code written for an AI class at Rutgers University. They provide C# code for different players and strategies, including a minimax player.

…but we’re not using minimax

On a random hunch I decided to try writing a bot without using minimax. I wanted to see how far I would get with (simple) heuristics and sound thinking.

A first sketch of the battle plan looked like this:

- If we’re seperated, use a quick but fairly good way to make good use of our available space

- If we’re not seperated:

- If there’s a move which does seperate us

- And will result in us having more space

- Make that move

- Otherwise: move towards the opponent

- Avoid draws if possible:

- Try your hardest to avoid a crash with the opponent if the opponent has no other spaces left to go

- If the opponent does have other spaces to go to, avoid a draw if it doesn’t negatively impact us`

Surprisingly, this code was working fairly well… A minute later I had implemented a small improvement:

- If we’re seperated, use a quick but fairly good way to make good use of our available space

- If we’re not seperated: - If there’s a move which does seperate us - And will result in us having more space

- Make that move

- Otherwise: move towards the opponent: - Do not use euclidean distances but use a shortest path, this ensures the bast way to reach our opponent

- Avoid draws if possible:

- Try your hardest to avoid a crash with the opponent if the opponent has no other spaces left to go

- If the opponent does have other spaces to go to, avoid a draw if it doesn’t negatively impact us

And as a final edge, I added:

- If we’re seperated, use a quick but fairly good way to make good use of our available space

- If we’re not seperated: - If there’s a move which does seperate us

- And will result in us having more space

- Make that move

- Otherwise: move towards the opponent:

- Do not use euclidean distances but use a shortest path, this ensures the bast way to reach our opponent

- Check in all four directions: where is the nearest wall?

- What would happen if we go to this wall, would this seperate us from our opponent?

- And would we get more moves in our space?

- And can we get to that wall faster than our opponent?

- Go to that wall and trap him!

- Avoid draws if possible:

- Try your hardest to avoid a crash with the opponent if the opponent has no other spaces left to go

- If the opponent does have other spaces to go to, avoid a draw if it doesn’t negatively impact us

Thanks to this trick, when we’re faced with a situation like this (we’re blue):

We will react accordingly:

“Ha ha, trapped you…”

This rudimentary bot has been doing very well and even scored in the top 30 for some time (alas, the ranking graphs have been taken offline, otherwise I would embed it here). However, a lot of players have been improving their code lately, causing me to drop back in the 100s.

Some peculiar problems

Lately I’ve been observing some interesting cases which can occur. You could call the first one the chamber or gateway problem.

Take the following map (we’re blue):

Since moving to the left would not seperate us from the opponent (he can still reach us by going around below), the old code would make us close in on him by going right:

However, once this happened, smarter opponent bots would rush to the little hole:

“Drats! I’m trapped now.”

Remember the definition of articulation vertices above? A final check I implemented looks at those little “gateways” and checks if our opponent can reach those faster than us, and if this would result in us being blocked off with less moves. If such a gateway exists, it’s better to go the other way.

A nice example (on a difficult map) of the bot in action, the map starts of like this (we’re blue):

A few moves later, and our bot has to make a choice:

It avoids the bad choice, as does our opponent. Not that the old version of the code would move us closer towards our opponent as well, as there is now possible separating move. (You might think that moving left separated us from our opponent, but this is only the case when our opponent is stupid enough to move right. Our bot now avoids “being trapped in a little box together”.)

A few moves later, and we make a choice again:

Again, we pick the best choice, and a few moves later:

This is a sure win.

A second problem deals with avoiding obvious stupid mistakes. The following game demonstrates some good fighting between the two players, but at the end, my bot (red, don’t worry, the gifs are repeating) makes a horrible mistake:

I modified the code once more to avoid this situation.

You could call the last problem the game of chicken problem. If you don’t know what the game of chicken is, the description from Wikipedia might help:

The name “Chicken” has its origins in a game in which two drivers drive towards each other on a collision course: one must swerve, or both may die in the crash, but if one driver swerves and the other does not, the one who swerved will be called a “chicken,” meaning a coward; this terminology is most prevalent in political science and economics.

The following game demonstrates the problem:

Can you see what’s happening here? The blue player plays it safe and moves out of the way early on. However, this causes the red player to end up with more space. If one of them moves out of the way, the other one wins. If they both don’t move, they draw. Figuring out when to crash (and draw), or when it’s better to move is a difficult challenge, especially for minimax strategies which often try to play it safe, as shown above.

In conclusion

Many strategies I’ve discussed before and others are posted on the contest’s forum.

Let’s look at a few more games to close things off…

In this game: my bot (blue) loses, but it puts up a good fight:

Here is a game where our bot does well. The opponent moves upwards and our bot confidently moves forward, trapping him in less space:

In this game, our opponent “chickens out” and moves away from us. We use this opportunity to trap him, knowing that we can use more space. Once trapped, the opponent doesn’t use his space optimally as well:

All in all this was an interesting and fun journey. My high rankings seem completely behind me though, but I’m glad I tried something different instead of following the obvious road. If you’ve been trying to write a bot as well: I hope you had a great experience as well, otherwise I hope you’ve enjoyed reading this little overview. I might talk about minimax and other mentioned topics again some time. Also: I should’ve started sooner taking a serious look at this contest. I get distracted too quickly :).

The contest organizers also put together a Youtube video showing some matches. It’s interesting to see how bots either try (or fail) to trap each other, and how the use the available space.